9th September 2019:

‘The Ultimate Question’ - what role should NPS play in brand evaluation?

The 56 Degree Insight team are excited to share the results from our survey of 16 iconic Scottish brands - the 2019 56DI Scottish Brands Index survey. This will be an annual survey which adds a Scottish flavour to brand evaluation – a unique addition to the Scottish marketplace. Each week we will take a look at one of the key metrics.

This week we consider advocacy and loyalty with a focus on the Net Promoter Score (NPS) approach. We take a slightly different tack from usual, considering some of the criticism levelled at this well-known metric and reflecting on its appropriateness for measuring Scottish brands.

Background

The Net Promoter Score (NPS) quickly rose to popularity after its creator Fred Reichheld published his article “One Number You Need to Grow” in the December 2003 Harvard Business Review, followed by his book in 2006 entitled “The Ultimate Question: Driving Good Profits and True Growth”.

Reichheld proposed that the percentage of customers enthusiastic enough to recommend a brand was a strong measure of brand loyalty or, as he put it, their ‘willingness to make an investment or personal sacrifice in order to strengthen a relationship’.

His analyses illustrated how loyalty measured in this way was directly linked to a company’s profitable growth. By sticking with a brand, loyal customers reduced the company’s costs to acquire new customers and the most loyal customers acted as advocates for the brand willing to ‘put their own reputations on the line’ to recommend the product or service.

The ‘Ultimate Question’…

NPS took the business world by storm. It was recorded using a single, straightforward question (see below), the score was simple to calculate with no complex algorithms required, and the result – a single number that could be tracked over time - was easy to understand, making it popular across businesses from time-poor senior executives to frontline staff.

In his paper and subsequent book, Reichheld presented analyses which demonstrated how well NPS correlated to business growth, using data on levels of growth for companies across a range of sectors. Going further, his results suggested that NPS was as good as or better at predicting growth than other commonly used measures of customer experience such as satisfaction levels.

The world of business loved the simplicity of NPS and the clear message it provided – to grow they needed more promoters and fewer detractors. It quickly became popular, adopted by many big corporations as a Key Performance Indicator (including over two thirds of Fortune 1000 companies). The approach was applied in different contexts, sometimes focused on a particular product, sometimes on individual transactions in a customer journey (e.g. a phone call or visit to a shop) or sometimes to measure loyalty to the brand as a whole, with customers asked to take everything they had experienced, seen or heard about the brand into account.

While originally conceived as measure of customer loyalty which could be used to support customer experience improvements, in the 15 years since Reichheld published his paper, NPS started to appear everywhere including customer satisfaction research, user experience studies, employee satisfaction studies and as a way to measure brand health.

Concerns and criticisms of NPS…

With its rising popularity, NPS and how it is being used has been criticised by some...

Predictive of growth?

Perhaps most fundamentally, academics have challenged Reichheld’s assertion that NPS is a strong predictor of growth, with research suggesting other questions related to loyalty such as levels of satisfaction or likelihood to repurchase are equally effective. Indeed, their analysis suggests that a combination of data from several questions to produce a composite index can be much more predictive of the future performance of a business.

If we refer back to Reichheld’s original 2003 paper we can see that his evidence is based on the performance of companies in six industries between 1999 and 2002 (“financial services, cable and telephony, personal computers, e-commerce, auto insurance, and Internet service providers”) and he recognises that the ‘would recommend’ question is not the best predictor of growth in every case. Indeed, his paper included recommendations for alternative questions. However, with the passing of time, it appears that these caveats and suggestions on different measures have not been top of mind for many NPS users.

Also, the world of business has changed dramatically in the 20 years since the data used in Reichheld’s paper was collected, so it would not be surprising if the factors which can predict the success of a brand have also evolved (in 1999 only 13% of us had Internet access and social media did not exist!).

Technical difficulties...

Other criticisms focus on the technicalities of the approach itself – the question wording, the 11 point scale and how the data is analysed and used.

A common concern voiced is that the question can be asked in situations where it is a little abstract or, worse, completely irrelevant. For example, the likelihood of recommending a particular brand in some low engagement situations (e.g. buying insurance, tyres or anti perspirant) may be low simply because it’s a topic most people would be unlikely to spend time talking about with their friends or colleagues. In other situations, the user of the product may not be the person who makes the purchase decision. Therefore, the question on whether the user would recommend it is irrelevant to future growth – this issue is particularly prevalent in a B2B context.

Concerns have also been made on how the data from the NPS question is used. Some have suggested that the rule used to designate consumers as either Promoters, Passives or Detractors is arbitrary. Identical NPS scores can be obtained from very different distributions of responses while small ‘tweaks’ to the analysis approach (e.g. including those who provide a response of 8 out of 10 as Promoters) can result in different outcomes.

Related, with its global popularity, users have noticed variations in how the NPS question is answered by different nationalities. For example cultural differences mean that Americans are more likely than Europeans to provide ratings at either end of the 0 to 10 scale while Europeans are more likely to provide responses closer to the middle of the scale (for example providing a 7 or 8 to reflect their happiness with a brand). This could lead to issues when comparing results between markets in a multi-country programme or using benchmarks which originate from different countries.

Comparability between results can also be an issue when NPS is collected using different survey approaches or in different contexts – for example results tend to be more positive in interviewer administered surveys than in self completion. Also, on average, results are more positive when asked about specific transactions than about the overall brand and results tend to be most positive when asked of recent customers rather than of a broader audience such as people who are aware of the brand. Given these differences caution needs to be taken when results from different sources are compared as there is a risk of not comparing like with like!

An NPS obsession?

A further area of concern relates to how NPS has been used (or misused!) in some organisations. There is a risk that businesses become obsessed with their NPS score – adopting it as a KPI at the heart of their business, including it in corporate plans as the central measure of business success and linking its improvement to bonus schemes. This could lead to a loss of sight on other important measures of business success or the risk of staff doing whatever it takes to achieve the improved NPS needed to get their bonus (at worst ‘gaming’ the system so that the least satisfied customers aren’t invited to provide their feedback).

An obsession on NPS as a KPI may also lead to ‘measurement for measurement’s sake’ when more effort should be placed on diagnosing the problems and taking action to improve what customers experience and think of the brand.

Indeed, in his 2003 paper, Reichheld recommended that the NPS questions should be followed by questions to “unearth the reasons for customers’ feelings and point too profitable remedies” but this sound advice is often not followed, or the responses collected to follow up question are not used to their best effect.

“You don’t fatten a pig by weighing it” Anon

Scottish Brands Index

When developing the 56 Degree Insight Scottish Brands Survey, we included the NPS question as one of our measures. Given its widespread use as a metric to gauge brand health we felt that it could be a valuable addition to our measurement of brand strength and, mindful of the criticism the measure has received, the survey provided us with the opportunity to review its applicability in the context of Scottish brands.

Our survey was undertaken during June and July 2019 using Kantar’s Scottish Opinion Survey, providing a representative sample of the Scottish adult population in terms of geography and demographics. Some 2,000 people were interviewed and asked a range of questions about a cross-section of Scottish consumer-facing brands – 16 in total:

To make survey length manageable, around 500 respondents provided their opinions about each brand. As well as being asked about likelihood to recommend each brand, respondents were also asked about brand awareness, trust, innovation, performance, prospects for the future and the extent to which they portrayed Scotland in a positive light. Over the course of August and September we are examining responses to all of these metrics and then finally provide our combined score to reveal the leading Scottish brand among the 16 we tested.

Brands were selected carefully; all were consumer-facing, some longer established than others and coverage spanned a range of sectors – transport, food and drink, utilities, financial services and sport. The 16 brands were key players within these sectors but obviously we were unable to cover all brands – however our selected brands represent a good cross-section of different types of brands in the Scottish marketplace.

How do our Scottish brands perform?

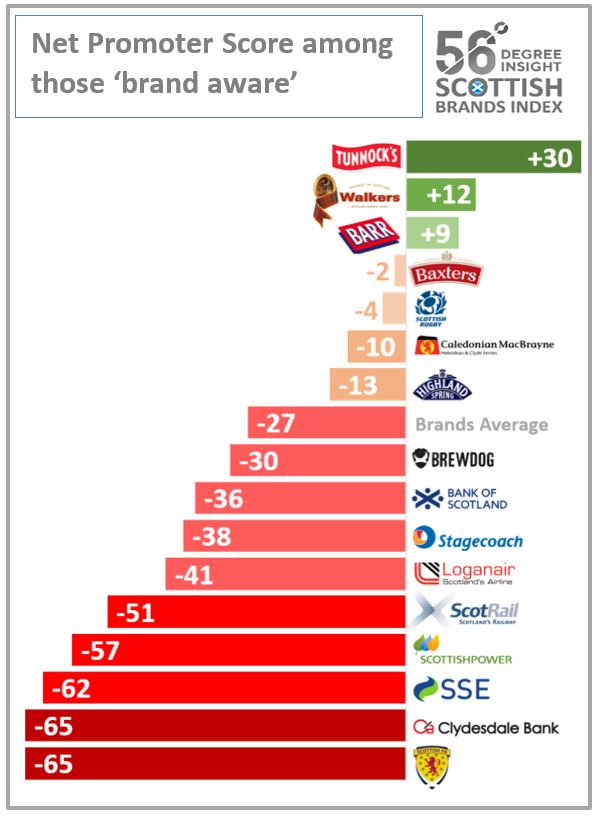

The results for our 16 brands using the standard NPS groupings and score are shown below. Note that for this analysis we just included those respondents who were familiar with the brands in question (i.e. excluding any who hadn’t heard of them or gave a response of Don’t Know at any of the preceding questions).

In general, the order of results is broadly similar to that seen with the other metrics used with the highest share of brand promoters and lowest share of detractors recorded for the food and drink brands. However, comparing the detail, there are some notable discrepancies. For example, Tunnocks tops the NPS ranking with a score of 30, well above any of the other brands, yet this brand had a lower ranking when it comes to Innovation (4th place). In contrast Brewdog achieves a negative NPS score and fairly low ranking which is in contrast to its top ranking for Innovation and its position as the fastest growing of the brands included.

So, while advocacy levels are clearly important, in themselves they don’t appear to provide a complete view of what makes a brand strong or a measure of growth potential. While consumers may only be willing to recommend those brands which they have a strong loyalty to, this measure does not necessarily capture other dimensions of the relationship such as how much they trust the brand, if they feel it is innovative or has a great chance of future success. And, of course, none of these measures necessarily capture the unpredictable ‘external’ factors which impact on business growth such as regulations, taxes or the cost of commodities (e.g. Walker’s profits were hit by the rising price of butter).

Some of the more ‘technical’ points which have been made regarding the effectiveness of the NPS question may also be impacting on the results seen for Scottish brands.

Firstly, it is important to note that this survey asked consumers to think about their overall views on each brand (rather than a specific transaction or product) and it included an audience covering both customers and others familiar with the brand but not necessarily users. These two factors are likely to result in a less positive rating than would be obtained in a survey of regular customers recording views after they have just sampled a new product (e.g. tasting a new Brewdog beer or travelling on a new high speed ScotRail service). Considering the context of our survey is important when interpreting what may otherwise be seen as rather negative results.

Secondly, when we look at the distribution of responses across the 11-point scale (see below), we see some clear ‘spikes’ with high proportions of respondents selecting the highest and lowest options and the mid option of 5. This was particularly the case for those brands in sectors which may be considered to be lower engagement: for example, about a quarter of consumers (24%) rated the energy providers with a score of 5. We suggest that this result is a reflection of low levels of interest in the energy category, with consumers unlikely to recommend their energy supplier to a friend or colleague because energy suppliers was a topic they were generally unlikely to ever speak about. It might therefore be argued that it would be more appropriate for those people who select the middle box to be considered as ‘Passives’ rather than ‘Detractors’.

Looking at the responses in this level of detail also shows how large proportions rated many of the brands with a score of 7 or 8. Whilst on face value this seems like a positive endorsement for the brand, these answers would not be taken into account in the NPS calculation as these consumers are classified as Passives.

If however the NPS approach was to be ‘recalibrated’ (defining Detractors as a rating of 0 to 4, Passives as 5 to 7 and Promoters as 8 or more) to reflect our more ‘European’ tendency to give mid-scale ratings, the picture painted would be clearer with a greater degree of discrimination between the brands (see below).

In conclusion

Our review of NPS and analysis of the results to the ‘single question’ suggest that this measure can play a part in the measurement of brand strength.

When analysis is focused on those who are close enough to the brands in question to give a valid view, their willingness to recommend can help us to understand their loyalty to the brands. However, advocacy is just part of the picture and best used alongside other metrics such as trust, innovation and expectations for the future.

Our analysis suggests that how the results from the question are used needs to be reconsidered as the standard NPS score may miss important details. This is especially the case when we are dealing with brands in sectors where levels of engagement tend to be lower. In these cases, consumers not expecting to talk enthusiastically to friends and colleagues about a brand does not necessarily reflect a lack of loyalty. We also need to reconsider how to define a brand Promoter whilst reflecting cultural differences. There is evidence that Europeans (including Scots!) have a greater tendency to provide fair to middling scores when we actually feel very happy with the brand.

These learnings will be reflected in the development of our final Index results to be published later this month – we will adopt a slightly different means of illustrating ‘positive advocacy’ as part of the overall Index creation.