26 November 2019

Political micro-targeting, fake news and boomer memes……..anything to worry about?

With just under 3 weeks until the UK general election, today’s blog looks at the potential issues arising from the increasing use of micro-targeting in political online advertising and some of the changes being made in the face of rising concerns.

Many of us first became aware of the use of targeted digital advertising in political campaigning in early 2018 when the Cambridge Analytica (CA) data scandal hit the headlines. The scandal focused around the misuse of personal data during the 2016 US presidential election when the personal details of 87 million Facebook users were used, without their permission, to develop the psychographic micro-segments used in extremely targeted online advertising from the Trump campaign.

The CA scandal was big news given the illegal use of personal data and the massive scale of the data breach, but it also brought the increasing use of micro-targeting in political campaigning to the fore.

Soon after the scandal erupted, in April 2018 the IPA (the UK’s advertising trade body) called for a moratorium on the use of micro-targeting in political advertising. The IPA’s principal concern related to the lack of transparency in the approach. In their president Sarah Golding’s words “very small numbers of voters can be targeted with specific messages that exist online only briefly. In the absence of regulation we believe this almost hidden form of political communication is vulnerable to abuse.”

The concerns raised by the IPA reflected a wider growth in concerns over digital campaigning approaches with some commentators going as far as suggesting that the approaches used could threaten the integrity of our democratic processes.

Cause for concern or just a sign of the times?

Are these valid concerns, or do we need to accept the use of these approaches as an inevitable consequence of our changing media landscape?

Over the last decade voters across every demographic have greatly increased the amount of time they spend online, especially on social media platforms, whilst readership of newspapers and viewing terrestrial television has declined.

So, it is natural that the political parties feel that they need to be online and on social platforms too.The approaches available also appeal to campaigners as they allow them to communicate tailored messages to defined demographic groups, within tightly defined geographic areas and within a precisely defined time period. The price tag for these approaches is much less than the use of more traditional media and requires a lot fewer people than knocking on doors. It might be argued that these approaches should be welcomed by the public, as we only see communications which are relevant to who we are and where we live - and if we wanted to we can easily dismiss them.

However, the concerns raised by commentators focus on two key areas. Firstly, there is the problem highlighted by the IPA relating to the lack of transparency – how do we know what political parties and other campaigners are spending their money on and communicating to small groups within the population? Secondly, there are worries over the accuracy of the information being communicated in advertising. While the claims made by campaigners through mass media such as party election broadcasts or press interviews are visible to a wide audience, allowing for any questionable claims to be spotted, debated and independently fact checked, there are concerns that a micro-targeting approach could fuel a rise in exaggerated or false claims.

Over the last month a number of the tech giants have taken steps to respond to these rising concerns:

One of the strongest responses has come from Twitter who introduced a complete ban on targeted political advertising last week. The ban covers all ‘political issues’ ads and paid for tweets by candidates. Twitter’s CEO Jack Dorsey announced the ban at the start of the month citing his view that “political message reach should be earned and not bought”.

Following this statement, Google announced last week that it would also be introducing a ban on the targeting of election ads based on a people’s political affiliations and that the uploading of doctored videos or “demonstratable false claims” on YouTube could result in a ban.

And tackling the specific issues related to the accuracy of the messages delivered in online advertising, last Wednesday Snapchat announced that they would be starting to fact check all of the political ads they run.

No change at Facebook

The vast amount of data Facebook holds about its user’s interests, social connections and attitudes allows targeting to go far beyond the more basic demographics possible on other platforms. However, while pressure is mounting, Facebook have stated that they have no plans to limit the use of their platform for targeted political ads or to bring in any forms of fact checking.

In the US, the Trump campaign (who spent $21m on Facebook ads since last May), contributed to the debate last week as their digital director Gary Coby argued against any limits on targeting on the platform, stating that “this would unevenly hurt the little guy, smaller voices, & issues the public is not aware of OR news is NOT covering.”

With the rising calls for increased visibility of online advertising, in 2018 Facebook introduced an online ads library which provides access to every political advertisement posted on Facebook and Instagram, together with basic information on who is seeing each ad and details on the total spend on digital advertising by political parties and other campaigning groups.

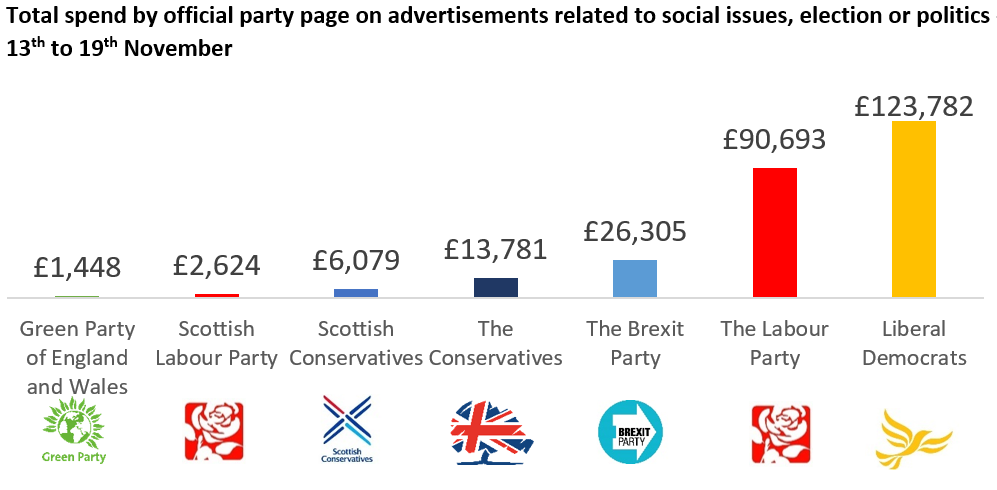

A review of the ads running in the UK during the last week reveals some significant differences in the amounts spent by our political parties on Facebook and Instagram ads. Levels of spending by the Liberal Democrats and Labour Party were much higher than for the Conservatives. In Scotland, the Scottish Conservatives spent the most during this period while the Scottish National Party and the Scottish Greens spent nothing.

The library also allows us to see the advertisements running and key information on who has seen them, revealing some interesting insights:

Liberal Democrats:

Below we see two Liberal Democrat ads which were running from 19th November, one encouraging voters to vote Lib Dem to stop Jeremy Corbyn and the other to vote Lib Dem to stop Boris Johnson. Apart from swapping the names and colours used in the bar charts, the wording and format in each advert is identical. However looking at who has seen each advert, the targeting is clearly very different with the call to stop Corbyn directed most heavily at men aged 25 to 44 while the call to stop Johnson is most heavily targeted at women aged under 35. The basic geographical details given shows that both ads were mainly only seen in England but it is likely that the geographical targeting was much more precisely aimed at people living in marginal constituencies.

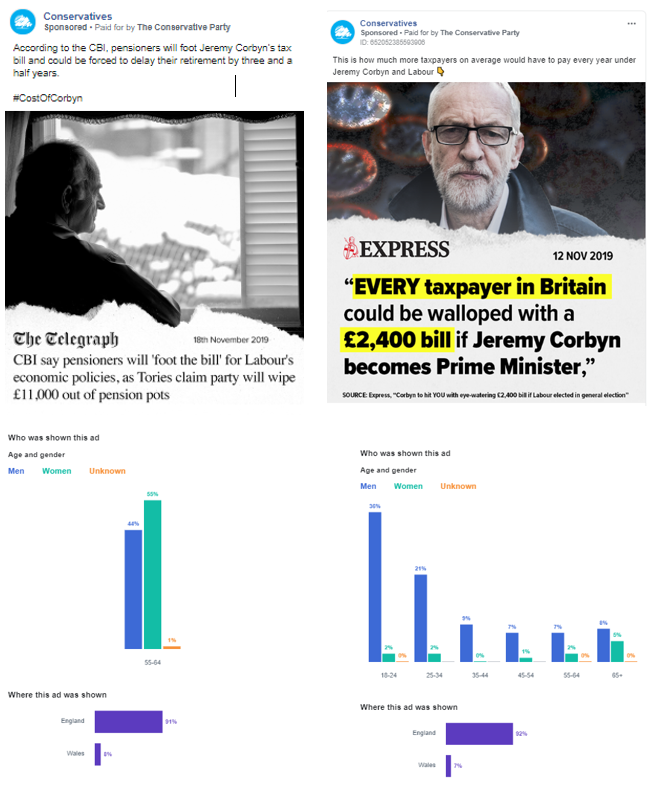

Conservatives:

The ads below from the Conservative party illustrate how different messages can be targeted at different demographic groups. The ad on the left shares the headline from an article in the Telegraph about the potential negative impact of Labour policies on pensions and was targeted at the 55 to 64 age band, in particular women. The ad on the right, shares a headline from the Express on the potential impact of Labour’s policies on tax bills and was targeted at a much younger, male demographic. Again, both of these adverts were almost entirely seen by people living in England.

Notably, the claims made in both of these headlines were challenged by the independent fact checking charity Full Fact (see https://fullfact.org/). Their comment on the £2,400 bill headline was that “this figure is largely meaningless as the calculations and assumptions behind it have a number of flaws.”

Scotland:

Turning to Scotland, below we compare two ads targeted at the Scottish population, on the left an advert from the Scottish Conservatives which ran from 14th to 16th November and on the right a Scottish Labour Party advert which ran from 18th November.

No details are available on the geographical targeting within Scotland but the basic demographic details show how the Conservatives advert was aimed more at men, particularly those aged 45 to 54, while the Labour advert targeted younger voters, in particular women aged 18 to 24.

Are the platforms going far enough?

Facebook’s Ad Library certainly goes some way to improve the openness of political advertising by giving the visibility needed by journalists, watchdogs and other interested parties to spot advertisements which are spreading misinformation.

However, given the speed that information can spread online, there is still a likelihood that misinformation will spread and have an effect before the fact checkers have had an opportunity to spot and flag inaccuracies. As the famous expression below alludes, falsehoods spread more quickly than the truth on social media so there is a risk that the corrections to inaccurate adverts never reach the audiences who saw the original messaging (the greater speed of lies was proven in a study by MIT in 2018 which found that false claims on Twitter travelled 6 times faster than true claims!)

“A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots.”—Mark Twain

Moreover, while attention is currently focused on the use of paid for online ads, organic, not paid for social media content such as the sharing of posts which originate from official party pages may present an even bigger challenge. The accuracy of the information in these communications is completely uncontrolled and there is no form of tracking or archiving of these communications.

During the current election campaign, we have seen the rise of approaches which seek to increase engagement in these posts and the likelihood of those who view them sharing them, even if they do not support the messages being communicated. An example is the technique called Boomer Memes when the content of a post or video is deliberately made to look basic, unprofessional or just a bit ‘cheesy’ to stimulate levels of sharing and discussion. The below post from CCHQ on November 12th was considered to have used this approach to gain traction, generating a great deal of conversation and sharing including mentions and clips on numerous television shows, blogs and thousands of retweets (including the one opposite from comedian Matt Lucas to his 1 million followers).

Fuelling distrust and polarisation?

The extent that online advertising and the organic sharing of political messaging impacts upon voting in the forthcoming election remains to be seen. The amount of money spent online in the US by the Trump campaign and their strength of feeling against increased regulation suggests that these approaches are working for them, but other commentators are very nervous of the potential losses for democracy when misinformation is spread. Without regulation, these forms of communication could fuel the rising distrust we see in politics and accelerate the polarisation of views seen in the UK during the last 3 years of Brexit debate.

As we approach 12th December it will be interesting to see how online communications play their part and no doubt there will be much further debate and evaluation of the impact of these approaches in the future. Watch this space…